Introduction

In mainstream historical narratives, Yuan Shikai is often remembered as an opportunist: the man who crushed revolutionary hope and attempted to crown himself emperor. His name evokes betrayal, power politics, and the failure of China’s early republican experiment. Yet this binary portrayal—hero or villain—fails to capture the complexity of his historical role. Especially in the realm of education, Yuan’s legacy deserves deeper analysis. While his political ambitions drew criticism, his efforts in reforming China’s educational system and promoting practical learning were not only significant—they were visionary for their time. By analyzing his educational policies through the lens of nation-building, this essay argues that Yuan Shikai should also be viewed as a strategic modernizer whose contributions laid the groundwork for China’s transition into a modern state.

I. Cultural Foundations: Reform Rooted in Tradition

Yuan’s origins in Xiangcheng, Henan Province—a region steeped in Confucian values—are not just biographical trivia. They offer insight into how traditional culture can nurture reformist ambitions. Unlike many reformers who openly broke with the past, Yuan integrated Confucian pragmatism into his modernizing agenda. This synthesis of old and new is perhaps one of the most underappreciated aspects of his leadership.

It is tempting to dismiss his reforms as administrative measures driven by political calculation. But doing so overlooks how his personal background and regional identity may have shaped his long-term view of national development. Yuan’s respect for order and hierarchy did not contradict his belief in the need for a skilled, educated citizenry; rather, they coexisted in a vision of controlled but forward-moving progress.

II. The Architect of Education Reform: Between Vision and Pragmatism

Yuan’s role in abolishing the imperial examination system in 1905 is often attributed to the broader reformist tide of the late Qing. However, his active involvement and early recognition of the system’s limitations reveal more than just political alignment—they show strategic foresight. Unlike radical intellectuals calling for total westernization, Yuan sought to restructure Chinese society from within, replacing ritualistic learning with skills necessary for national survival in a world dominated by imperial powers.

His influence in creating provincial universities and drafting model charters was not mere formalism. By establishing schools like Shandong University and supporting counterparts in Zhejiang and Hunan, Yuan standardized and legitimized the idea of modern higher education in China—a transition that required not only resources, but political courage.

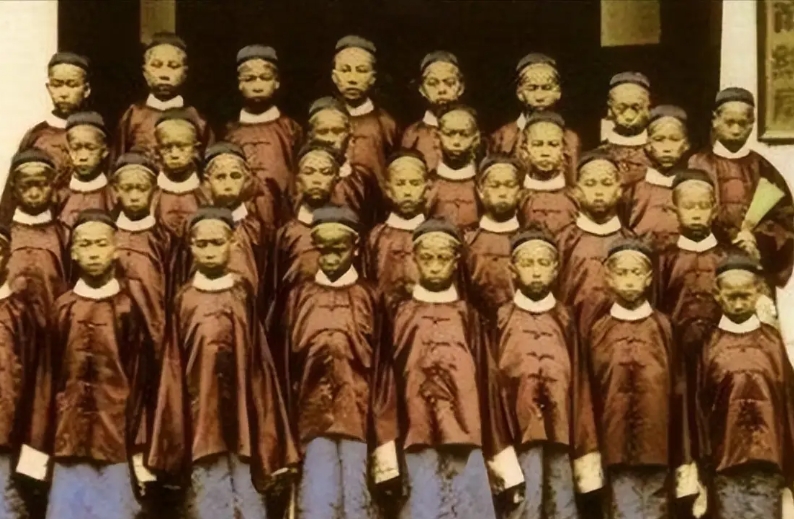

Yuan Shikai implemented new policies by establishing teacher training colleges

III. Education for Utility: A Nation-Building Strategy

What sets Yuan apart from many of his contemporaries is his commitment to education as a tool of statecraft, not just enlightenment. His investments in teacher training, industrial education, and women’s schooling were aimed at cultivating a functioning modern bureaucracy and productive workforce, rather than creating philosophical or political debate. This utilitarian vision may not align with liberal ideals, but it was arguably more effective for a fragile nation on the brink of collapse.

His founding of agricultural and vocational schools across Zhili Province was not merely economic policy—it was a recognition that without food security and skilled labor, constitutional ideals would remain meaningless. In this sense, Yuan’s modernization was rooted in reality, not ideology.

IV. The Paradox of Progress: Reform from the Center of Power

It is worth noting the inherent contradiction in Yuan’s legacy: a conservative reformer, pushing for national transformation while fiercely holding onto centralized authority. Unlike reformers who worked from the margins, Yuan’s changes came from within the machinery of the state. This made them more institutional, but also more vulnerable to being swept away by political upheaval.

His 1912 School System Order, which marked the formal beginning of compulsory elementary education in China, was revolutionary. Yet it came from a man whose later attempt at monarchy discredited his legitimacy. This paradox raises a critical question: Can progressive change endure when led by those unwilling to surrender power?

In Yuan’s case, the answer is mixed. While his monarchy attempt collapsed, his educational frameworks persisted in later regimes. This tension between personal ambition and public progress is central to understanding his legacy.

Yuan Shikai supported normal school students in studying abroad for further education

V. Reframing Yuan Shikai: Beyond the Tyrant-Visionary Binary

To reduce Yuan to either a power-hungry autocrat or a misunderstood reformer is to flatten the texture of history. His story is less about moral categories and more about the messy realities of national transformation. He was a transitional figure—not quite a democrat, not fully a traditionalist—struggling to navigate the disintegration of empire and the birth of a modern state.

Crucially, his belief in state-guided modernization aligns more with East Asian developmental states (like Meiji Japan or Park Chung-hee’s South Korea) than with liberal Western models. From this comparative perspective, Yuan appears less an aberration and more an early example of authoritarian modernism in Asia—a model where education, discipline, and state-building go hand-in-hand.

Conclusion: A Legacy in Need of Reassessment

Yuan Shikai’s political downfall has long overshadowed his role as a builder of modern China. Yet his work in education—especially his efforts to replace archaic institutions with functional, forward-looking ones—offers a counter-narrative to the trope of the failed emperor. As modern historians, we are challenged not to excuse his power plays, but to understand how even flawed leaders can leave behind durable, positive change.

By integrating tradition with reform, authoritarianism with modernization, Yuan Shikai occupies a unique space in China’s historical development. Recognizing his contributions to education is not an act of political rehabilitation—it is an act of intellectual honesty. In the story of modern China, Yuan is not merely the man who tried to be emperor—he is also the man who helped educate a nation.