I met Yuan Shikai twice.

The first time, he stood in a battlefield of footnotes, stern and statistical. The second time, he strolled through a narrative fog, speaking in whispers and contradictions. Neither encounter gave me the full picture. But together, they changed how I read history—and how I read people.

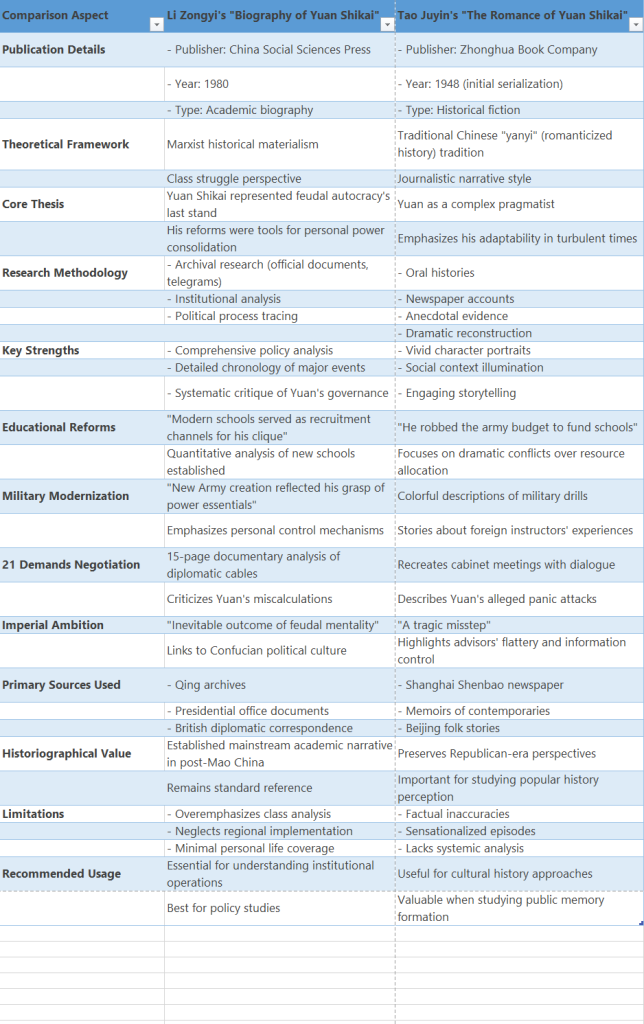

Li Zongyi’s Yuan Shikai Biography was my first gateway. It was dense, methodical, and sharp-edged, like a cold scalpel carving away myth. I followed Li’s dissection of Yuan’s political maneuvers, his bureaucratic reforms, even his insulin doses as he battled diabetes in the final years of his reign. It felt like watching a machine being taken apart. Fascinating, yes. But also distant. I admired the precision, but I couldn’t hear a heartbeat.

Then I opened Tao Juyin’s Romance of Yuan Shikai. It read like a novel, full of reconstructed dialogue and imagined moments: Yuan hesitating before signing an edict, sighing in candlelight, eating too many dumplings at a banquet. At first, I was skeptical. Was this still history? But soon, I found myself leaning in. Tao didn’t offer answers—he offered questions, scenes, moods. And slowly, Yuan the mechanism became Yuan the man.

Reading both books side by side was like watching two painters at work: one using a ruler, the other using shadow. Li taught me the discipline of historical distance—how to track sources, challenge assumptions, follow cause and effect. Tao reminded me why history matters in the first place: because it is made by human beings who are rarely consistent and never simple.

Their contrast unsettled me. I wanted to choose a side. Was Yuan a reformer who miscalculated? Or an opportunist who stumbled into greatness? But maybe that desire—for clarity, for a clean moral verdict—was the very impulse history should resist. I started making a table: on one side, policy data and tax records; on the other, local stories I’d gathered from a visit to Yuan’s hometown in Henan—where villagers debated whether to serve him chrysanthemum tea or vinegar if he walked in today. Somehow, both lists felt true.

Through this process, I realized that my job isn’t to decide who Yuan was, but to stay curious about how people see him—and why. To sit with contradiction, rather than solve it. That shift in mindset spilled into other areas of my life: how I handle disagreements, how I question what I read, how I listen more closely when the story sounds incomplete.

My bookshelf still holds both books. Their spines are worn, their margins full of scribbles and arrows that contradict each other. I used to think one of them would help me “understand” Yuan Shikai. Now I see they helped me understand something else: that truth, especially historical truth, often lives not in consensus, but in conversation.