Most people visit ancient monuments with a camera. I brought a drone, 200 gigabytes of storage, and an unusual fascination with unicorn horns.

At the Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum, I led a project to digitally reconstruct a royal funeral route built six centuries ago. Using UAV photogrammetry and 3D modeling software, we mapped the entire Sacred Way—its triple-arched gates, towering stele, and solemn stone beasts—with a resolution sharp enough to spot centuries-old tool marks. But I wasn’t just building models. I was reverse-engineering imperial messaging.

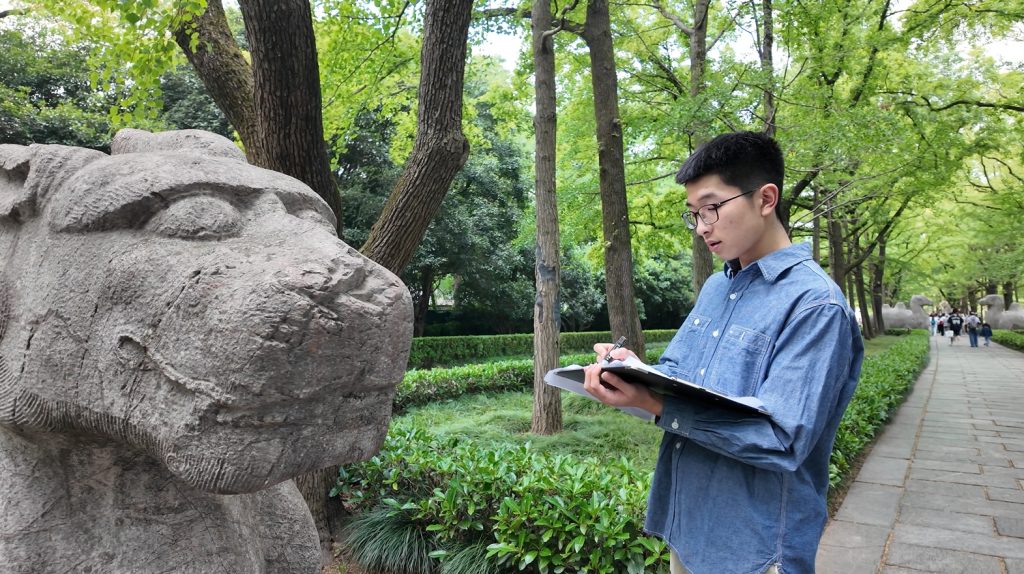

Take the xiezhi: a mythical beast with a single tilted horn. According to legend, it rams the guilty and spares the innocent. Ours had a horn slanted exactly 15°—which, I discovered, matched Ming-era court rituals linking spatial symmetry with moral order. In other words: justice, encoded in limestone.

Where the Past Leaves Its Lines

As I compared our scans with 15th-century architectural codes, the whole site began to speak. This was not just a tomb; it was propaganda—stone geometry telling a story of cosmic hierarchy, political legitimacy, and eternal rule. And I was the kid decoding it.

This project taught me that history isn’t buried—it’s encrypted. You just need the right tools, patience, and sometimes, a drone. I’ve learned to treat ruins like arguments, carvings like footnotes, and monuments like primary sources that forgot they’re being watched.

Pixels of the Past

History is my way of seeing what others overlook—and sometimes, of talking to ghosts through pixels.

Sketches of History