The Temple of Heaven, the largest surviving ancient sacrificial complex in the world, stands not only as a priceless cultural treasure but also as a vivid testament to the survival philosophy and civilizational journey of the Chinese people. Built in 1420 during the Ming dynasty’s Yongle reign and thoughtfully renovated under the Qing emperors Qianlong and Guangxu, the Temple commands a solemn presence that seems to whisper stories stretching across centuries and dynasties.

In February 2018, I took my first photo with the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, reflecting on the relationship between traditional rituals, political institutions, and architectural landscapes in Chinese history.

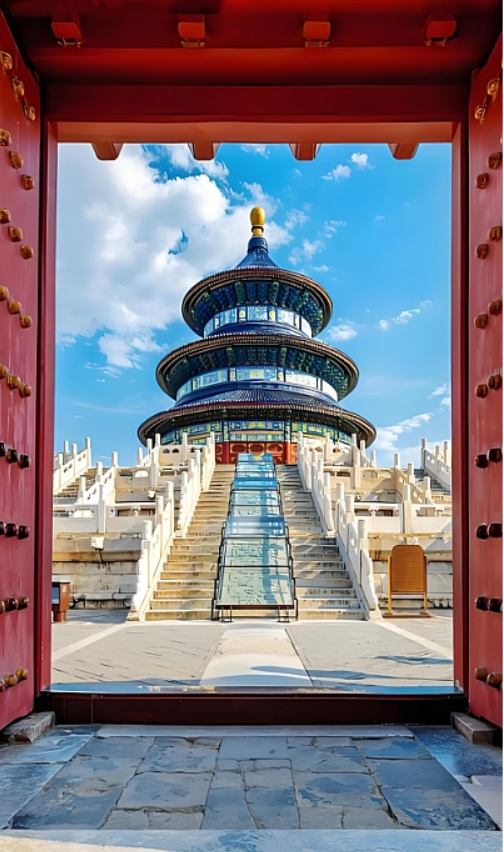

At the heart of this architectural marvel is the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, a structure over 600 years old that could probably tell a few tales if it could talk. Its distinctive three-tiered circular roof, topped with a pointed apex and cloaked in shimmering blue glazed tiles, symbolizes the vast heavens above and the gravity of the divine mandate below. Inside, twenty-eight towering Nanmu wood columns are arranged in concentric circles, each with its own symbolic role: four “Dragon Well” pillars, each a whopping 19.2 meters tall and 1.2 meters in diameter, represent the four seasons; twelve golden columns stand for the months of the year; and twelve outer columns correspond to the traditional Chinese hours. This precise arrangement reflects the ancient architects’ remarkable understanding of nature’s rhythms and the cosmic order—think of it as the Ming and Qing dynasties’ version of “design thinking.”

Beyond its architectural splendor, the Temple of Heaven was the sacred stage where emperors performed rituals to pray for bountiful harvests. These rites were far from mere pageantry; they embodied the spiritual aspirations and collective hopes of the Chinese people. Passed down through generations, these sacrificial ceremonies reached their peak during the Ming and Qing dynasties, when the Temple became the epicenter of state rituals. Twenty-two emperors conducted 654 major sacrificial rites here—a staggering number that speaks not only to imperial dedication but also to the enduring power of faith and harmony in governance.

The Temple is also a remarkable symbol of cultural coexistence and integration within China. During the Qing dynasty, the imperial rites preserved Han Chinese ritual traditions while skillfully weaving in religious and cultural elements from Manchu, Mongol, and Tibetan peoples. This fusion reflects the pluralistic unity that has long been a hallmark of Chinese civilization.

Today, the Temple of Heaven and its Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests stand as iconic emblems of Chinese culture. Their architectural design, embodying the ancient cosmological concept of “round heaven, square earth” and aligned along a solemn central axis, captures the spirit and vitality of Chinese civilization. Visitors from around the globe flock here, eager to admire the Temple’s architectural beauty, artistic elegance, and profound cultural legacy.

Ultimately, the Temple of Heaven reveals not only the grandeur of ancient imperial sacrificial rites but also the deep-seated collective belief in unity and harmony that has shaped the Chinese nation throughout its long history. It acts as a living historical scroll, narrating the moving story of China’s multiethnic integration and transmitting cultural energy across time and space—reminding us all that architecture can be much more than stone and wood; it can be a dialogue between heaven and earth, past and present.